Foraging, or the art of gathering wild food to eat, is thrifty, fascinating and a brilliant excuse for a good walk. It can seem like most of nature’s bounty is out for the picking in summer and autumn. But even in winter, when the British landscape seems bare at first glance, there’s plenty of wild food to be found, from the trusty nettle to nutritious seaweed.

Inspired to find food for free this winter? Be aware that foraging is legal in England, but only if you’re collecting for your own personal use. If the plant you like the look of are on private land, it’s always best to ask permission to pick them first. Whatever you collect, take only what you can eat, and a leave plenty behind for wildlife (and other hungry pickers).

Don’t forage near roads, to avoid polluted plants. Never pick or eat anything you can’t 100% positively identify. And if you’ve never foraged before, stick to very easily identifiable crops, such as blackberries or nettles, and see if there’s a local wild food course you can take, taught by an expert– it’s much easier to recognise plants if someone shows you their characteristics in person, and you’ll learn local plants and secret hotspots near you to forage at. My guide to what to forage for in winter in the UK includes beginner-friendly, easy to identify wild foods to get you started.

What to forage for in winter in Britain

Hazelnuts

Easy to find and identify (if the squirrels haven’t eaten them), hazelnuts grow in hedges and woods in papery green casings and are sometimes still around at the beginning of winter. If you find them whilst the nuts are still green, you can ripen them at home. When roasted they are amazing mixed with chocolate and made into brownies or a spread.

Crab apples

Small, rather sour crab apples don’t look immediately appealing but they are delicious when cooked up, and they’re ripe from October onwards. They’re high in pectin – try making a classic crab apple jelly with them.

Sweet Chestnuts

Is there a more cosy, wintery snack than roast chestnuts? They’re a favourite foraged find in autumn, but you can still find these delicious nuts in winter, hence their association with Christmas. Look for their spiny green casings on the ground – they’re not be confused with horse chestnuts (conkers), which are inedible.

Alexanders

Alexanders are part of the carrot family and are one of the easiest greens to find growing wild in winter. They have wide stems and leaves that can all be cooked and that are young and tender around January in parts of southern Britain. Alexander is a plant best picked after an expert has shown you how to find them, as they belong to the same family as hemlock, which is poisonous. The stems are delicious when steamed.

Nettles

Ah, the classic foraging favourite – the humble nettle. Cooking nettles removes their sting, and makes them harmless, filling and very good for you, packing more vitamins than spinach. Nettles are around for most of the year, so they’re ideal for picking in winter when other goodies are scarce. When picking nettles, wear thick gloves and pick only the young, healthy leaves.

Wood Sorrel

Wood sorrel is not to be confused with common sorrel, although this can also be foraged for and eaten. Delicate wood sorrel resembles clover, with three heart-shaped leaves. It’s most distinctive for its deliciously sharp, lemony taste. I love wood sorrel in salads or eaten with fish.

Wild garlic

The delicious, pungent and jewel-green leaves of wild garlic shoot up at the end of winter in March, a lovely sign of the warmer spring weather to come. They are easy to identify, with wide flat leaves and an unmistakable garlic smell. They crop up in big bunches on the forest floor and lend themselves perfectly to homemade pesto. A nice one to forage for with children.

Chickweed

As its name suggests, chickweed is a tough weed that is often found in gardens and veggie patches and which grows in winter. It tastes rather like spinach and the young leaves are great in salad or made into soup. Look for the distinctive hairy line that runs down the stem, and white, star-like flowers.

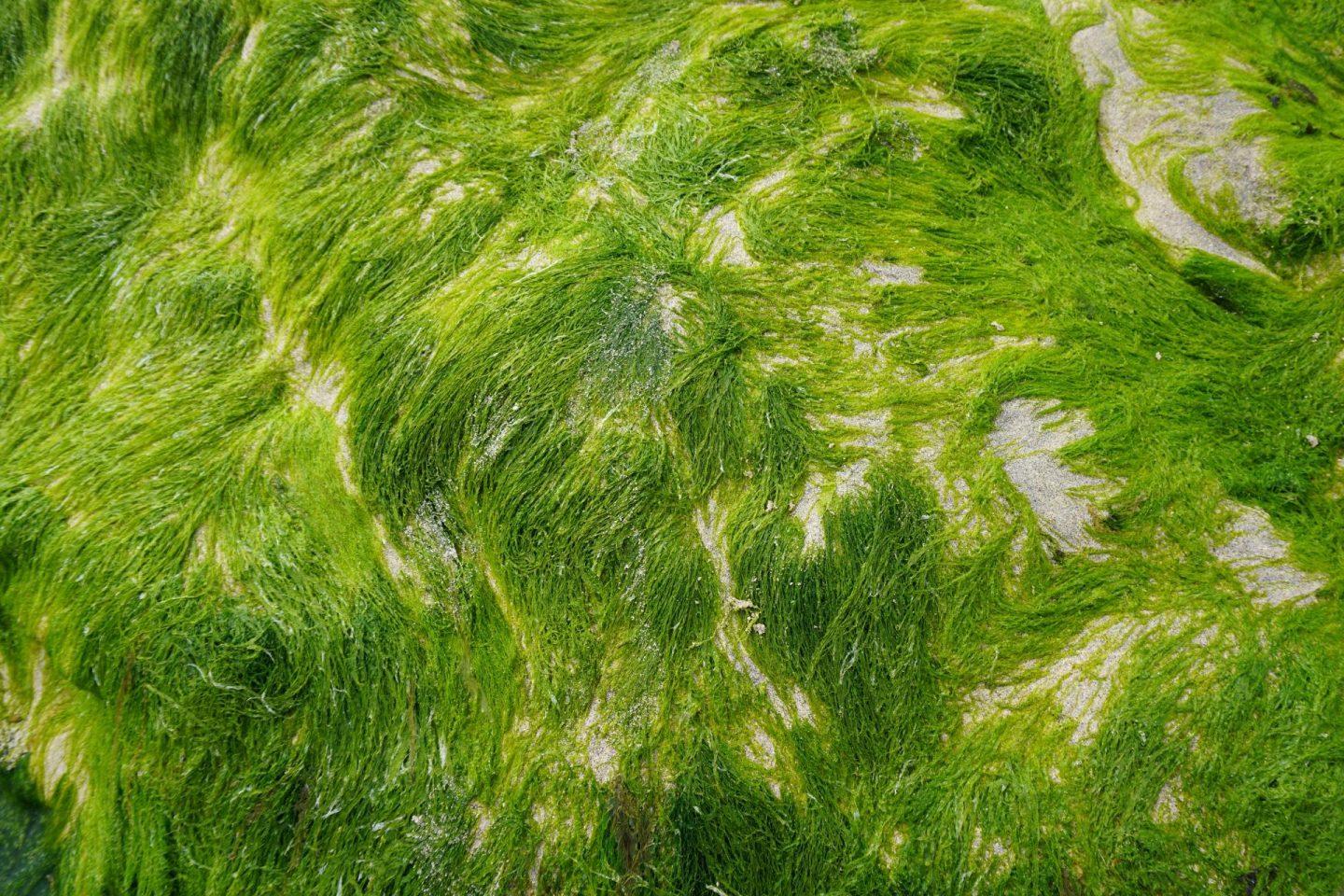

Seaweed

Seaweed might seem intimidating to identify or a little confusing to cook with if you’ve never foraged before, but it’s actually a great place to start, especially in winter, as there are 20 edible varieties of seaweed in British waters and they’re easy to ID and available year-round. They’re also all full of minerals, vitamins and protein. Have a look for a regional guide – I use Rachel Lambert’s seaweed foraging guide in the south. My favourites to find and cook with are lurid green gutweed, which is great dried in the oven and sprinkled on salad, and sea spaghetti, which is easy to spot and great cooked up and eaten like its namesake pasta.

Sorrel should only be eaten in small quantities as it contains high amounts of oxalic acid which is not good for your kidneys. A small handful in a mixed salad is OK.

I’ve been studying this lately! Awesome post!